The Return of Realpolitik

The collaborative international order has been exposed as skin-deep

Towering Columns

In The Spectator, Michael Gove says we are leaving a world of idealism, in favour of pragmatic - if pessimistic - realism.

Donald Trump’s presidency is the harbinger of many things – a vibeshift in our culture, a dismantling of bureaucratic and therapeutic government, a commitment to what the Silicon Valley entrepreneur Alex Karp calls a ‘Technological Republic’. But it also marks a return to a bleaker, starker, more pitiless world landscape. The ideal of a rules-based international order, where multilateral institutions restrain states pursuing their self-interest, has proved to be a false hope. Instead of a world operating according to the dreams of Antonio Guterres or Ursula von der Leyen, we are back to a world closer to that of Thucydides in which the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must. It’s not a new world order but a based world outlook.

As a politician, I indulged in as many false hopes as anyone. I hoped regime change in Afghanistan and Iraq might see democracy spread across the Middle East. I imagined that the Arab Spring and the fall of Gaddafi would mark the eclipse of tyranny and terror. I sat around the cabinet table when we vowed with Boris that Putin must lose. So I am a reluctant realist, a chastened idealist not so much red-pilled by MAGA as schooled by unending history…

…We might think that peace with Putin is appeasement that will only encourage Beijing, but Trump believes it is a pivot away from a war the West cannot win to preparation for one it cannot afford to lose. We might think that everyone gains from a rules-based international order. But for President Trump, the deal appears to involve America paying to uphold that order – while the rules on everything from tech regulation to carbon emissions are being set by others in ways which weaken the US.

On ConservativeHome, Sam Bidwell says full assimilation, not integration, should be the goal of immigration policy.

[A]ssimilation [as opposed to integration] is a process by which newcomers to a society become indistinguishable from their peers. An assimilated migrant is not merely non-criminal and economically successful; they belong to the nation as a whole, fully adopting its customs, norms, and habits. The assimilated migrant will feel deep ties to the nation and its history, beyond the mere institutional loyalty expected under the integrationist model. We have managed successful assimilation in the past. Few in modern Britain could identify which of their peers is descended from Huguenot refugees or Flemish wool merchants. These small, culturally compatible groups assimilated into the fabric of British society, adopting the customs, habits, and practices of the broader population. Even more recently, Britain integrated thousands of Irish migrants during the period of industrialisation, when rapidly expanding urban centres attracted labour from other parts of the British Isles.

Today, many of our urban centres, including cities such as Liverpool and Birmingham, are home to significant populations of Irish descent, who are largely indistinguishable from their peers. The Irish migrants who came to Britain in the 18th and 19th century have now largely assimilated – though not without significant difficulty along the way. It is not impossible to imagine that such a process could take place again, with respect to a limited number of culturally-compatible migrants. Through close contact, individual effort, and intermarriage, we might expect to see a subset of the newcomers become fully assimilated over the course of a few generations.

But mass migration of the scale, pace, and diversity that we now face renders assimilation impossible – and our system is not designed with assimilation in mind. The millions who have come to Britain over the last few years cannot be expected to assimilate and, indeed, have not been compelled to do so…

…Assimilation is a higher standard than the simple test imposed by the integrationists. Perhaps this is why successive governments have chosen to abandon promotion of assimilation altogether. It expects more from those who come to this country, and forces confrontation with norms and practices which conflict with our own. This is not necessarily easy – but it is worthwhile.

In The Atlantic, Derek Thompson says the global pandemic may have pushed a generation of young people to the political right.

Another way that COVID may have accelerated young people’s Rechtsruck [rightward shift] in America and around the world was by dramatically reducing their physical-world socializing. That led, in turn, to large increases in social-media time that boys and girls spent alone. The Norwegian researcher Ruben B. Mathisen has written that “social media [creates] separate online spheres for men and women.” By trading gender-blended hangouts in basements and restaurants for gender-segregated online spaces, young men’s politics became more distinctly pro-male—and, more to the point, anti-feminist, according to Mathisen. Norwegian boys are more and more drawn to right-wing politics, a phenomenon “driven in large part by a new wave of politically potent anti-feminism,” he wrote. Although Mathisen focused on Nordic youth, he noted that his research built on a body of survey literature showing that “the ideological distance between young men and women has accelerated across several countries.”

These changes may not be durable. But many people’s political preferences solidify when they’re in their teens and 20s; so do other tastes and behaviors, such as musical preferences and even spending habits. Most famously, so-called Depression babies, who grew up in the 1930s, saved more as adults, and there is some evidence that corporate managers born in the ’30s were unusually disinclined to take on loans. Perhaps the 18-to-25-year-old cohort whose youths were thrown into upheaval by COVID will adopt a set of sociopolitical assumptions that form a new sort of ideology that doesn’t quite have a name yet. As The Atlantic’s Anne Applebaum has written, many emerging European populist parties now blend vaccine skepticism, “folk magic” mysticism, and deep anti-immigration sentiment. “Spiritual leaders are becoming political, and political actors have veered into the occult,” she wrote.

New ideologies are messy to describe and messier still to name. But in a few years, what we’ve grown accustomed to calling Generation Z may reveal itself to contain a subgroup: Generation C, COVID-affected and, for now, strikingly conservative. For this micro-generation of young people in the United States and throughout the West, social media has served as a crucible where several trends have fused together: declining trust in political and scientific authorities, anger about the excesses of feminism and social justice, and a preference for rightward politics.

On his Substack, Matt Stoller says the Trump Administration has so far followed the robust approach to antitrust reflected in the Biden-era merger guidelines.

So far, in cases such as Kroger-Albertsons and Tapestry-Capri, ten courts have found the [new merger] guidelines persuasive. Beyond that many conservatives came to accept the arguments about market power; influential right-wing scholar Todd J. Zywicki called the new guidelines ‘moderate’ and ‘reasonable’ at a Federalist Society event. Today, Steve Bannon calls himself a “neo-Brandeisian” who thinks Lina Khan should have had a lot more power.

Still, there was another open question about whether the second Trump administration, having taken over from an administration they disdain, would seek to roll back this achievement, or would have continuity with what Trump did in his first term. Wall Street, and the old guard scholars like Herb Hovenkamp, thought they would go back to a neoliberal and merger friendly set of guidelines.

But they didn’t…

…A few weeks ago, the Trump Antitrust Division challenged a significant $14 billion tech merger, Hewlett Packard - Juniper Networks, which shocked and frustrated Wall Street. Mergers are down 30% in January compared to last year, which, while mostly due to financing costs and tariff uncertainties, isn’t unrelated to concerns over antitrust…[t]he reaction has been what you’d expect, with anti-monopolists supportive and libertarians, well, not so much. Wall Street merger arbs, the people who speculate on consolidation, are unhappy. So are big tech lobbyists, big tech friendly Silicon Valley venture capitalists, and big law defense lawyers on both sides of the aisle.

On his Substack, Rian Chad Whitton reviews the argument of Angus Hanton in his book “Vassal State”, which portrays Britain as a subordinate nation of the United States.

Hanton is right to challenge some on the right, whose concern for mass immigration does not extend to foreign ownership of British capital. During Maggie’s tenure between 1979 and 1991, foreign ownership of British stocks never breached 13%. Now it is 60%. Thatcherism was built to deal with the challenges of a bloated, inefficient but still significant industrial great power. Today, Britain is still bloated, and inefficient, but is hollowed out and dominated by foreign capital.

Of course, foreign influence in Britain is far from limited to the U.S. The chair of the Conservative Party’s 1922 Committee, Bob Blackman, actively supports India’s incumbent BJP party and advocates for their interests in parliament. We have MPs who seem to care far more about either Israel or Palestine than domestic affairs. Our rich list is dominated by foreign oligarchs, most of whom are not American. Labour’s anti-corruption minister lost her office because of charges brought to her in Bangladesh. It seems right that if we fight the influence of a relatively benevolent Western hegemon, we’d question our general xenophilia at large.

Hanton’s remedies to U.S. dominance are not particularly strong. He calls for Britain to stop sell-offs and purchase golden shares in strategic champions. I am sympathetic to this, much to the chagrin of my Thatcherite coevals. But they do have a point about our track record in state development not being fantastic. He says we should invest more in our people. To be honest, I don’t think this is a solution. The British elite believe in the power of education more than any other group on earth as far as I can tell, and it does us precious little good. He also suggests we should do more research and development spending. This is all well and good, but big R&D budgets tend to come after the establishment of big conglomerates, not before.

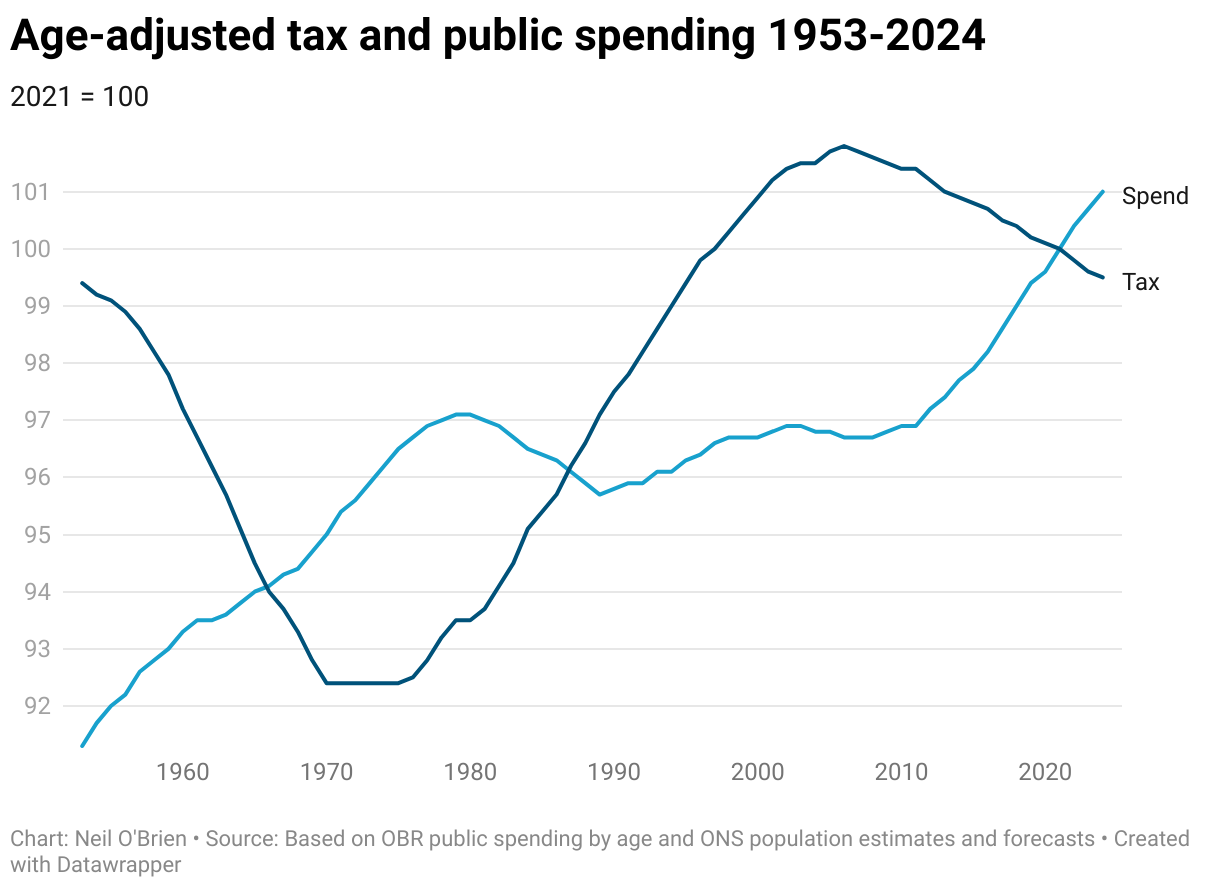

On his Substack, Neil O’Brien examines the impact of demographics on public spending pressures.

What would have happened if we’d had today’s patterns of public spending and tax with yesterday’s demographics? Obviously in practice the pattern of spending by age will probably have been a bit different, but the basic fiscal lifecycle of taking out a bit as a child, paying in as an adult, then taking out again as a pensioner is an enduring one.

The graph below holds spend by age constant and changes spending and tax receipts in line with the demographics of that year, with 2021 used as the base year.

You could have achieved the same service for each age group with quite a lot less cash in the past, mainly because of the smaller proportion of pensioners. Despite the larger number of kids, you could have spent about 9% less in 1953 compared to 2021, and still delivered the same service for each age group.

Demographics made it steadily harder to raise tax revenues from 1953 to 1970, but then then steadily easier from the mid 70s to the financial crisis. You could think of this as the period where the boomers had their career peaks. From 1979 to 1990 demographics were helping Mrs Thatcher on both the tax and spending side.

In contrast, since 2010 we have been running up the down escalator. More older people has been pushing spending up, while the working age share falling has been bad for tax receipts. (The boomers retiring, if you will).

Wonky Thinking

For the Institute for Public Policy Research, Josh Ryan-Collins argues in “The Demand for Housing as an Investment” that supply-side changes are not enough to solve Britain’s housing crisis. Rather, measures need to be taken to prevent the buy-up and inflation of the housing stock for speculative investment.

The UK housing market is characterised by a housing-finance feedback cycle, whereby increasing financial flows into housing generate rising prices and expectations of future rises, which in turn generate more speculative demand for housing as an investment, and so on. Policy makers need to carefully consider what types of interventions can break this powerful dynamic. Marginal reforms in discrete policy spheres are unlikely to do so.

For many years policy has focused on new construction to increase supply. Whilst this may be effective in reducing housing costs in certain areas, more emphasis should be focused on repressing investment demand for housing with the aim of releasing a portion of the existing stock for either first-time buyers or conversion to social rent where housing need is greatest. Such supply can be bought onto the market much more quickly than new build.

Local authorities (LAs) could be given powers to limit use or tenure change that would mitigate against affordability, for example the conversion of primary residences or long-term PRS lets to second homes or short lets. They and other social landlords or community housing associations could also be given right-offirst refusal to buy and, where needed, renovate PRS properties that stressed BtL investors may choose to sell or where landlords are unwilling to upgrade rental properties to Decent Homes Standards. LAs could also be given new compulsory purchase powers to purchase early-stage private sector developments, that have been delayed due to the housing downturn, at prices that would render the existing permission viable at minimal profit margins and convert these to social rented housing. These interventions will require financial support from government – Homes England could consider raising the 10% acquisitions cap on the Affordable Homes Programme (AHP) – and, in the longer term, the creation of a public housing corporation/bank.

Compulsory and permanent mortgage insurance and longer term fixed-rate mortgages for first-time buyers should be introduced to bring down the cost of higher loan to value (LTV) ratios for first-time buyer mortgages. Alongside this, HMT and the Bank of England/FCA should consider lowering LTV ratios for BtL mortgages to reduce the volatility of the mortgage and housing market, and repress speculative demand during upturns or when interest rates are low.

An annual property tax could be introduced, replacing Council Tax and Stamp Duty, that would considerably reduce investor demand for housing and free up potentially hundreds of thousands of properties to better meet housing needs. If this is not feasible in the short term, SDLT and Capital Gains Tax on additional homes should be significantly raised.

Further research on the demand for housing as an investment could be undertaken to examine in more depth the role of individual cash-buyers and capital market actors in buying residential property as investments, in particular since 2008, and their sensitivity to interest rate changes; the efficiency of the use of existing housing units (for example, excess bedrooms, under-occupation); and the extent to which landlords pass on increases in costs (including those due to interest rate rises and tax rises) to tenants and/or exit the PRS.

The Tony Blair Institute published “Making UK Industrial Strategy Work: A Hard-Headed Approach Guided by Green Industry”. The report explores the challenges for the UK in capitalising on net zero opportunities, while admitting that green technology will not lead to a boost for British manufacturing.

This is a fiercely competitive policy area, where the world’s largest economies are using their power to gain a strategic edge – creating disruption for others in the process. China has been the catalyst, having spent more than a decade tightening its grip on critical-mineral supply chains and using public funds to cement its dominance in green technologies. The United States and the European Union, unaccustomed to playing second fiddle, have scrambled to respond – sending shockwaves through global markets. The US Inflation Reduction Act was bold and expensive, triggering a global race to pull the green industries of the future onto US soil. Now, as President Donald Trump’s administration pivots back towards fossil fuels, the tide is shifting again. Meanwhile, the EU has taken a different tack, experimenting with tools such as its carbon border adjustment mechanism to shield its greening industries. But as Mario Draghi’s recent report makes clear, the EU will need to go much further to revive its sluggish competitiveness. The UK, like other open mid-sized economies, risks being buffeted by these shifting currents. But rather than mimicking the approach of any one great power, it must chart its own course – forging a competitive edge that plays to its unique strengths.

This will be a critical test for the new government. After months of declining business sentiment, its industrial strategy – due in the spring – will be a pivotal moment to reset the narrative. It will be a bellwether of the government’s competence, pro-business credentials and ability to deliver on its growth mission. But warm words about Britain’s future won’t be enough – the strategy must be hard-headed enough to convince the world that Britain is open for business. This report aims to support that effort with new economic analysis to inform prioritisation, a new strategic framework to guide decision-making and cross-cutting policy recommendations to lay the foundations for long-term success.

A hard-headed industrial strategy must be grounded in robust evidence, applied consistently across sectors – something too often lacking in the past. New analysis by Oxford Economics and the Tony Blair Institute helps fill this gap, offering fresh insights into the opportunities and challenges of the UK’s green economy:

Fully capitalising on the net-zero transition could provide a major boost to UK growth. In a best-case scenario, the green economy could grow from 0.8 per cent of GDP today to nearly 6 per cent by 2050, employing 1.2 million people – up from 200,000. This could lift the UK’s annual growth rate by 0.1 to 0.2 percentage points over the next 25 years, a vital boost at a time of sluggish growth. This upside potential is why green growth must be part of the government’s economic strategy.

Achieving these gains will be challenging. Success depends on the UK capturing market share in a wide range of globally competitive sectors, including electric vehicles (EVs), where the UK lags behind global leaders. The UK does not fully control its destiny in this race, but without a change in approach, these gains will not materialise. On current trends, the green economy is more likely to reach just 1.6 per cent of GDP by 2050, employing only 350,000 people – barely enough to offset the decline in carbon-intensive “grey” industries. Betting everything on green growth would therefore be a mistake. It must be a pillar of the UK’s growth strategy, but it cannot be the whole strategy. To succeed, the UK must cultivate multiple engines of growth and not skew its strategy too heavily towards “green”.

The green transition is unlikely to drive a revival of UK manufacturing jobs, but green services offer significant employment potential. Even in a best-case scenario, green manufacturing is expected to employ around 425,000 people by 2050, fewer than the 700,000 people currently employed in grey industries. This partly reflects structural trends: even if the UK manufacturing sector successfully navigates the green transition, it will likely continue to become more efficient and employ fewer workers over time. This should not downplay the importance of green manufacturing. Many of the strongest rationales for government intervention are focused on the manufacturing sector. Green manufacturing and services are also complementary: the more domestic manufacturing activity and clean power generation, the greater the opportunities for tied services. But as a service-dominated economy, it should come as no surprise that the UK’s greatest green growth and employment opportunities lie in green services, which could account for up to 4 per cent of GDP by 2050 and employ as many as 800,000 people. The government must be careful not to over-state the job opportunities from green manufacturing.

To position the UK for success, the government must break the cycle of past industrial strategy failures – incoherent, siloed decision-making that leads to zigzag policymaking. Since 2010, the average industrial strategy has lasted barely more than a year. This instability cannot continue. Businesses need a clear, consistent approach to decision-making to provide the certainty required for long-term investment. That is what this report’s new strategic framework is designed to deliver.

Book of the Week

We recommend Second Class: How the Elites Betrayed America’s Working Men and Women by Batya Ungar-Sargon. The author journeys through left-behind America to reveal the lives of the economically abandoned working class.

The class divide has become the defining characteristic of the American twenty-first century. Yet the working class is a cipher in American politics and media. Despite the fact that the largest share of Americans are working class, their voices have been essentially erased from the public sphere and public debate. How do American workers view their chance at the American Dream, their struggles and triumphs, and their place in American society? And what do working-class Americans want? What do their lives look like? Do they believe they have a fair shot at the American Dream, or do they think that the system is rigged against them? What does the American Dream mean to them?

…I spent a year travelling around the country interviewing working-class people to get their sense of whether they had a shot at the American Dream, and if not, what might make it more of a reality, or even a possibility. I spoke to people from across the political spectrum, people of different genders and races and family structures and religious creeds from all over the country. It is their stories you will read in what follows.

..A few things came up in nearly every one of the interviews I did, which also surprised me. The first of those was the value of hard work. I can’t think of a single person I interviewed who didn’t tell me that working hard is a value they learned as a child and is central to their identity. Work means dignity and independence and autonomy and pride. It means having something no-one can take away from you, even when work is scarce, even when the conditions aren’t ideal. The Marxist view of work as inherently exploitative, something people would ideally be freed from, has taken on new life on the American Left as well as the free-market Right, with ideas like Universal Basic Income. But the working-class Americans I spoke to over the past year didn’t view work as exploitative. They viewed the value of hard work through an almost spiritual lens, as though it were a precarious inheritance that continued to connect them to their parents, who as children they saw getting up every morning and going out to provide for their families. It is essential to how they see themselves as Americans, and a great source of pride, no matter what they did for a living.

Quick Links

Military chiefs told the Prime Minister he must raise defence spending to 2.5% of GDP before 2030.

The former commander of NATO called for the conscription of 30,000 British soldiers per year.

The Government has admitted that net zero policies will mean higher energy bills, at least in the short term.

The Government ran a smaller surplus than expected at the start of 2025, putting extra pressure on public borrowing targets.

Russia is in a current account deficit for the first time this year, meaning its exports are not financing its imports…

…But China’s exports to Russia have more than made up for the drop in Western exports…

…and most countries in the world now have China as their biggest trading partner.

Labour is exploring an “Australian-style” youth mobility scheme with the EU, alongside harmonisation on areas such as carbon pricing.

Labour would suffer its worst defeat in Scotland since devolution if a vote were held today, a new poll found.

The unemployment rate has hit 6.1% in London.

France has sustained a fusion reactor for 22 minutes, breaking the world record previously held by China.

The Government spends £8 million per year on interpreters for non-English speakers claiming benefits.

The Home Office refused to release data on how many deportations are prevented by commitments under the ECHR.

Japan has a higher percentage of older workers still in the labour force, reducing its need for immigration.

Microsoft announced the development of Majorana 1, a new chip that utilises a new state of matter and could underpin a quantum computing revolution.

Europe would be in a population freefall by 2100 without immigration, according to forecasts.

China has sold off $77bn of US Treasuries, leaving it with its smallest holding in 15 years.

The gap in belief in God between US Republicans and Democrats is at a historic high.